The sari as a concept has been interpreted in diverse ways for various audiences – a cultural symbol for Indian women everywhere or merely a popular tool used by Bollywood time and again for objectifying women in their films.

What a sari means to the ordinary woman is understood by how Bollywood uses it to further the various stereotypes it propagates through its female characters. How the sari becomes a tool of objectification when it comes to our infamous item numbers, or how it represents maternal affection through the maa stereotype – the mamta of whom the sari so envelopes; and finally, how the transformation from a typical ‘modern woman’ to a homemaker can be achieved by simply wearing a sari.

Tip tip barsa paani, paani ne objectification lagayi

The discourse on the problematic female representation in Bollywood is certainly endless. But there should be a place of honour in this discussion for the overly sexualised combination of the sari and item numbers. And the occasionally additional element of the very Bollywood-y barsaat that seems to expedite the romance between the protagonists. It’s difficult to narrow this list down – considering there are so many films that have used this draped piece of cloth to accelerate the oomph factor of their overall production.

So what do you do when it’s raining? Crave for a steaming cup of chai and hot pakodas, because same. But Bollywood will have you believe that monsoon is the season of getting it on. Because as the film Mohra would want you to know, what else is there to do other than scuttle away to an abandoned factory and get grooving with your guy! And my heart goes dhak-dhak simply imagining how Madhuri Dixit managed to keep all that keechad off of her gorgeous sari.

If you thought it was just the barsaat that was causing all that sizzle, think again. Because we have a whole lot of instances where the demand for water is nowhere except the thirst it is meant to cause.

The guardians of our Indian culture pedestalise the sari like the emblem of our sanskar, but Bollywood in its representation has successfully reversed this and managed to tarnish the sanskar-iness of it all and made it every sanskari mard’s wet dream instead.

To highlight how ridiculous the sanskar-iness of the sari plays out, Sayfty, an organisation that empowers and protects women from violence, came up with a unique concept: the ‘Super Sanskari Saree’. Presenting an “ultra-modest” collection of “r*pe-proof clothing for objects who want to be treated like women”, the site satirises the country’s absurd ways of victim-blaming and shaming. Offering a variety, from the ‘Ambitious Nari Office Saree’ to the ‘Acchi Bacchi Saree for Kids’, the website presents the harsh reality of the belief that the ‘modest sari’ supposedly does not objectify women.

Maa ka aanchal

Let’s take a detour from the grouse that we have with these item numbers and problematic representation. Don’t forget, pallu ke neeche maa ka pyaar bhi chupa ke rakha hai. There have also been filmmakers who have used the sari to further the idea of maa ki mamta.

Not very different from objectification per se, the sari has been the symbol of maternal affection for several of these films.

The universal maa of Bollywood, there must hardly be a film when Nirupa Roy played a mother and did not wear her iconic white sari. Because you’re not a self-sacrificial maa otherwise. And the actress without whom the list of Bollywood mothers will remain incomplete — Rakhee. Perhaps the reason her Karan-Arjun did not come was because they were bored of seeing their mother dress up in the same sarees over and over again. A rebirth may be the only way they could avoid having that talk.

The flag bearer of familial traditions, Rajshree, is famous for generating films that further the mother stereotype. Reema Lagoo — perhaps the 90’s equivalent of Nirupa Roy is no different in her attire as a mother. Dressed in a plethora of rich sarees that show both her standing in society and her mamta in the family, I wonder how the character would have turned out if she chose to dress herself in easier and more comfortable clothing.

The transformation from being a carefree bird to being more gharelu

Contrarily enough, while the sari when coupled with the right amount of paani and dhak-dhak can give off the required sizzle, it can also represent modesty if worn in the sanskari context.

As a medical student falling in love and having a child out of wedlock, Vidya (played by a brilliant Vidya Balan in Paa) does not find the need to drape a sari. Instead, she chooses to dress as what can be described as a liberating quirky goth — commando boots and flowy skirts.

But life as a doctor and a mother calls for some modesty policing in her attire. And what better tool to further this transition from a life of liberation and carefree behaviour to the life of a mother? Because there was absolutely no opportunity for her to go change into something more comfortable and more suitable to play basketball in… as the instructor of a summer camp.

The journey for all these characters from their unconventional original selves to their more mature and socially acceptable versions is complete simply by wearing the ‘more traditional’ sari.

The transition of Kajol’s character in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai has been called out for its problematic transformation countless times. But what is interesting to see here is that this metamorphosis into the conventionally ‘desired woman’ is achieved by simply draping a sari (while obviously becoming more sublime and demure in the process). Because if KKHH would have you believe, the way to a man’s heart is to stop behaving like your own carefree self and instead start dressing in a manner that matches his image of the ‘perfect woman’.

- Ladies first: 6 Indian TV shows with powerful female protagonists

- Hum honge kaamyaab: 15 historic moments for women in 2021

- ‘Female’ CEO; ‘female’ billionaire: why gendered job titles need to go

- Keepin’ it real: 7 influencers who make us feel comfortable in our skin

Subverting the sari

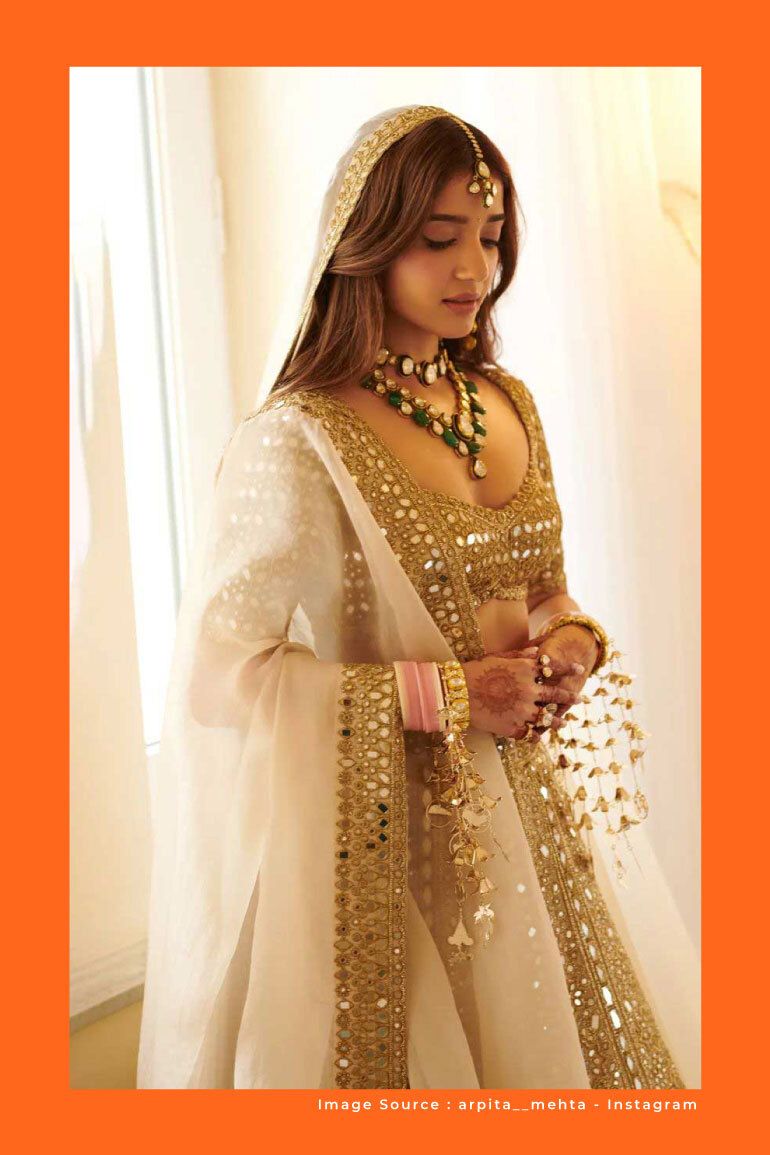

The sari in all its glory has also been a piece of cloth that supposedly hides flaws. Something that you can drape around yourself in the way you deem fit. Something that doesn’t discriminate between body types and something that can be worn in any manner you choose.

How the sari is a living, breathing garment is even more clear when we pick up examples such as the comment designer Sabyasachi Mukherjee made at a conference: “If you tell me that you do not know how to wear a sari, I would say shame on you.” There are more than 100 iterations of draping a sari in India, all utilitarian, emphasizing that the sari is not merely to be worn at cultural fests or at familial occasions.

Vidya Balan has been repeatedly chastised for her clothing choices from the moment she became an integral part of the film industry. From being body shamed for her portrayal of Silk Smitha in The Dirty Picture to being persistently questioned for her clothing choices in several other films, she has now arrived at the destination that most women are still journeying towards — being comfortable in her skin. She has managed to subvert all that criticism by choosing to don the sari – both on and off screen.

It is the manner in which she has chosen to embrace the sari that is representative of the elegance that this piece of cloth coupled with the intrinsic comfort you feel in your own skin can exuberate.

Women like Sarla Thakral have also managed to subvert this modesty policing and actually used the sari as a means to women empowerment. I’m sorry, who is Sarla Thakral?

So when Sarla Thakral — India’s first female pilot — flew the Grey Moth in the year 1936 at the tender age of 21, she chose to wear a sari. This was not a random fashion choice but a conscious one — one that has immense socio-cultural implications.

When we choose to wear trousers and pants to work, in a field considered ‘for men’ — like say, flying a plane, we are imitating a man. Essentially, we are being men and negotiating in a man’s world.

What Sarla Thakral reminds us is that it doesn’t have to be a man’s world. It can be a woman’s too. The cockpit would have remained a masculine space if Sarla Thakral chose to wear her husband’s pants. So when she stepped into the cockpit — wearing a cultural signifier of being a woman, she changed the cockpit to a gender-neutral space.

The politics of the sari

But let’s move on from the flag bearers of tradition and look at what the sari means to the public that it actually concerns — Indian women.

Let’s look at our Indian female politicians. A symbol of power, dominance and womanhood all coupled into one — the sari is the chosen attire for most of them. But whether this is a conscious choice to maintain the status quo or simply chosen by a process of eliminating all other options is to be debated. Because I wonder how this country would react to a female leader dressed in pants!

As much as this choice can be attributed to a statement of power, there can be an equally strong opposing factor that highlights a sense of submission. Submission to dress in accordance with how society perceives women leaders must look like.

The sari can be the patriarchal prison that women are imposed to — if we let the institutions that define this country make them so.

But it is important to remember what Sarla Thakral was trying to say all those years ago — to refuse the need to abandon traditions simply for their gender connotations. It can exude power if we want it to. Or become the tool that defines female dominance if enough characters of this sort are written.

And more importantly, it can be a metonymic of female strength — the one that does not need a man to tell her what she should wear.

And for the ordinary woman

A lot of the feminist discourse talks about how mandating the sari in several institutions is a means for patriarchy to regulate women’s bodies.

Schools and colleges continue to impose this modesty-driven unwritten sari code on teachers and professors. Yet they find these women sexualised, as the recent ‘blue-sari teacher’ case in Kerala proves.

The ability of the sari to accentuate a woman’s body has been exploited by popular media to the point where the garment has become eroticised. Considering the many impositions and policing that women have to bear, why does the onus of presenting modestly fall only on women?

I remember in school, the times when the entire student and teacher body would be busy prepping for an upcoming annual day, or any other cultural event. The D-day of these events would entail a much-planned-out and excessively fussed over entry of ‘honourable chief guests’. They were mostly men in positions of power that had some stake in the monetary well-being of the school. A lot of thought used to go into planning their entries into the event. But do you remember who used to be chosen for the crucial position of giving bouquets away? If your school was anything like mine back in the early 2000’s, a bunch of schoolgirls dressed up in sarees.

Back in the day, being chosen to wear the sari and present the bouquet was made out to be something of a privilege. Because it translated into being called pretty. With schools becoming more woke, this could be a dying tradition (one can only hope). But the notion, in retrospect, reeks of sexism.

The concept of a sari again comes into the forefront as the means to sexualise young girls — making them look older and more ‘desirable’.

More recently, I remember talking to my university professor, who guest-lectured in several other universities — many of which have the sari as a mandatory dress code for female professors. My first question to her was if there were any such prescribed guidelines for male professors? A formal shirt, ties, buttoned down blazers, or even a dhoti perhaps? Her answer: No.

But what this also makes me wonder is: what is the yardstick of modesty? The same aforementioned university in question penalises female students for first, their kurtis being too short and second, for not pairing their approved kurtas with a modest dupatta. So what is this criterion that defines modesty? The one that approves of the six-inch-midriff exposure in a sari but castigates the uncovering of the two-inch-neck?

Take Vidya Balan in Tumhari Sulu or Mission Mangal, or even Sridevi in English Vinglish. These characters are the perfect attestation to owning the sari as their preferred choice of clothing but also their character. I can’t imagine Sulu or Shashi without their sarees. The iconic way with which they’ve pulled it off beautifully as if it was always meant to be that way.

The essence of their womanhood, their homely responsibilities, their maternal concern, and their position as the glue that holds their families upright; the sari is the perfect signifier of all this and so much more.

Vidya Balan both in real life and in Tumhari Sulu is a brilliant testament to what the sari is to the ordinary woman. A piece of clothing that doesn’t judge, doesn’t have a size, and doesn’t discriminate. The sari envelops the essence that Sulu emulates — her womanhood, her ambitions, and her natural comfortable self. One who does not shy away from being true to herself — be it in her kitchen or in her workspace.

The sari has and continues to be flexible, to reflect the imagination of its wearer. But more than anything else, the sari is the choice to just be. Above the debate of objectifying or empowering, the sari represents individuality. The manner in which a woman chooses to drape her sari is representative of her own subjectivity; her own agency and the way she wants the world to view her.

You’re invited! Join the Kool Kanya women-only career Community where you can network, ask questions, share your opinions, collaborate on projects, and discover new opportunities. Join now.